by DavidSpratt | Oct 26, 2017 | ICT

Last month I introduced Communities of Practice, a model designed to help align business strategy with the evolving knowledge and experience of its people, while still taking advantage of the efficiencies that can be gained through more formal organisations and processes.

There are three elements that make up a Community of Practice. These are Domain, Community and Practice.

Domain

The common ground that inspires members to join, drives their learning activities and gives purpose and meaning to their activities.

Let’s take a simple example. Yours is a plumbing and gas fitting firm with offices across the country. The building boom has meant that Christchurch, Nelson, Auckland and Tauranga are seeing increased demand for the design and installation of sophisticated gas heating systems and appliances in new, architecturally-designed homes, shopping centres and offices.

In each of these main centres you have a mixture of apprentices, newly-qualified and experienced tradespeople working under a standard organisational structure with supervisors and a branch manager.

The domain in this instance is the design, selection and installation of new gas systems. The reason people join (purpose) is to share ideas and come up with best practice by taking advantage of the work that community members have done, whether in training at apprentice school, at their previous job or on the job last week.

The motivation (meaning) is twofold. To be recognised by your peers and to learn from the experience of others, in an environment where the company rewards these activities.

Community

Creates the social fabric for learning.

Our plumbers and gas fitters are in a mixture of locations and have a wide variety of experience and insights and formal learning. In reality though, they do not have a great deal in common other than their learning domains.

In our imaginary firm, Jim and Rod have a common cause when it comes to the knowledge they are sharing from Jim’s last project. Jim is sharing his ideas and experience from a job where he specified and installed the latest gas appliances from a new European supplier. Rod is about to install the same equipment on his next job and is worried about getting the specification wrong. He has never seen or installed the equipment before and the job has contracted delivery milestones and quality demands.

What I haven’t mentioned is that Jim only just qualified as a gasfitter last year. He finished his apprenticeship with another company in Dunedin and only just joined the Christchurch team in January. Rod, on the other hand, has worked for the Auckland branch as a supervisor for twenty years and is regarded as the top dog in the Auckland office.

Jim wears tight jeans and sports an indie-style beard, while Rod has a beer gut and listens to Led Zeppelin. In normal circumstances, these two vastly different people with seemingly nothing in common would never have come together for the betterment of themselves or their firm. The Community of Practice that the company has established means that knowledge and skills are now becoming a part of the fabric of how things are done at work regardless of location or status.

Practice

The Practice component of a Community of Practice is the point of action around which a community develops, shares and maintains its knowledge.

A Practice is built on establishing, recording and sharing formal methods (explicit knowledge) and practical experience (tacit knowledge). It delivers reusable and constantly evolving best practice while making room for innovation. It allows the firm to continue to constantly improve its standards regardless of changes to the organisational structure or the movement of staff.

Jim’s willingness to share his drawings and installation instructions and, importantly, to take the occasional phone call from Rod has created genuine, measurable customer value on his latest job. These drawings and connections also endure for all community members and the firm. This motivates staff, creates a sense of belonging and maintains competitive advantage for the company as a whole as it evolves in a tough, competitive market. This is the basis of Communities of Practice.

Part Three of this series covers the most important question of all. How do we break down the structural, cultural and political barriers that exist to Communities of Practice while maintaining the day-to-day organisational framework that ensures the business operates in the day to day?

by DavidSpratt | Sep 13, 2017 | ICT

A colleague from one of New Zealand’s emerging winners in the software development market tells me that, despite its success, he is concerned about whether he is utilising the very expensive specialists in his business to best effect.

He bemoaned: “It seems the bigger we get, the more time wastage we create.

“Our best people are already frustrated at the inefficiencies and are headed to the door.

“It’s hard enough finding top people without losing the best of the best to our competitors. We pay well. We have a great environment in our offices and our customers are blue chip – what am I getting wrong?” he said.

Many companies face the same problem. The business grows and people begin to disconnect, both from each other and from the business’ strategic direction. As silos are created by management, knowledge sharing and common approaches to problem-solving are replaced by “standards and procedures”. The business becomes burdened under red tape while its creative excitement seems to be drained of energy with every additional memo.

As entrepreneurs, we all know this story and understand that as businesses grow it becomes necessary to institute a level of structure to address complexity. While bringing order and control the unintended consequence can often be a stifling of the creativity and a growing structural inability to share ideas.

People in all sorts of organisations share their experience, learn new skills and create innovations. In larger, more structured organisations these learnings can often end up remaining in the head of the individual or local team, simply because business rules, targets and individual measures make sharing ideas counterproductive to the individual.

Communities of Practice

Emerging across the business world now are “communities of practice” as a means of ensuring that the skills, experiences and ideas of our staff are constantly shared and refreshed to the benefit of the participants and, vitally, for the business

An early exponent of Communities of Practice, US-based educational theorist and practitioner Etienne Wenger, has spoken about the challenge of restructuring organisations to improve performance while avoiding the destruction of innovative capital. In essence, he believed, communities could exist within an organisation and people continue to share and create new ideas regardless of the department or team they worked in. Knowledge and strategy, it seemed, could coexist without adding further inefficiency.

So how do we establish and run these communities? With tools like mobile phones, Skype and intranets it isn’t all that difficult. All you need are willing people, a common purpose and a point of focus.

These are three main components to be considered in establishing communities of practice:

- Domain

The common ground that inspires members to join a community of practice drives their learning activities and gives purpose and meaning to their activities.

- Community

A community creates the social fabric for learning. It brings together experts and learners while encouraging meaningful interactions – a willingness to share what is in their heads, for common goals and shared growth.

- Practice

The community needs a point of action, or practice, around which it develops, shares and maintains its knowledge.

By implementing Communities of Practice in the work environment, you can make a difference in how key teams operate… That helps increase efficiency and stops that talent walking out the door.

Next month, I will examine domains and communities in more detail.

by DavidSpratt | Jul 24, 2017 | Energy

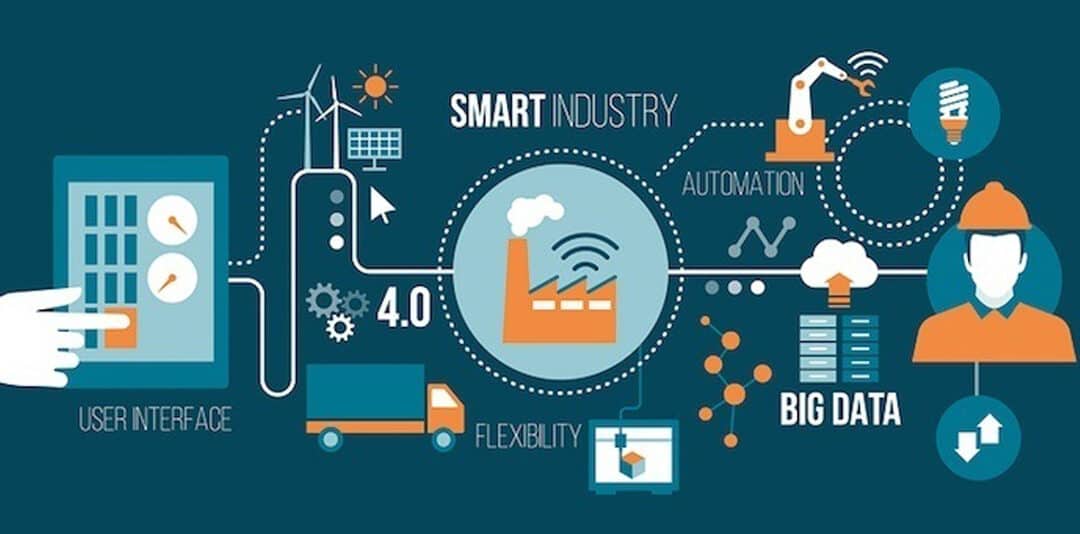

The boundaries between physical, digital and biological worlds are breaking down — giving way to a new world of computer based business known as cyber-physical systems. These cyber-physical systems are characterized by the merging of physical, digital, and biological realms in profound ways. Artificial intelligence (AI) serves as the primary catalyst of this transformation.

Klaus Schwab, Chairman and Founder of the World Economic Forum wrote:

We are at the beginning of a revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope and complexity … the fourth industrial revolution is unlike anything humankind has experienced before.

We have all heard this kind of hyperbole before. So why should this matter and what are local companies doing to address the issues?

Beyond hyperbole

It matters because we have already seen our lives changed by these tools in the most dramatic fashion. The last presidential election in the USA was directed affected by the use of AI.

These tools were used in identifying and directly addressing those electors who were undecided or felt strongly about key issues. These powerful compute engines, combined with good old-fashioned phone calls and door knocks, meant voters were either encouraged to vote by “people like them” who knocked on the door (e.g. young mum talking to young mum) or to not vote through messages directed directly to them about the futility of “rigged” elections.

Leveraging AI in the New Zealand Business Context

Politics and business are uneasy bedfellows so I will get back to the brief. How do Kiwi companies respond to international and local competitors who already understand and are leveraging artificial intelligence and bringing it to our competitive landscape?

Let’s start with energy. It is one of the most fundamental parts of any business. Most of us just focus on getting a cheap price for electricity or gas and then move on to running the enterprise day to day.

This approach just won’t work when machines are making the micro-decisions that can mean success and failure.

International Competition

Consider some of our major New Zealand computer companies. They are in a life or death struggle with public cloud providers like Microsoft, Amazon and Google. These gigantic multinationals have access to all the tools mentioned above and even deliver them “as a service” to companies everywhere. Competing with organisations like this is not just a question of having good people or getting the best price for inputs. It is about innovation and very, very careful monitoring of all the inputs and outputs, including energy.

One of the most brutally competitive battlegrounds is over the provision of data centre services to the business market. In the past ten years companies like Datacom and Spark have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in state of the art datacentres. These datacentres require huge amounts of energy to keep them running.

New Zealand’s advantage

New Zealand has a natural advantage because over 80% of our energy is created via renewable means. In the years ahead this advantage will become a cost and strategic advantage.

As the forth industrial revolution unfolds New Zealand’s energy advantage that will drive our strategic advantage in data centres. Don’t believe me? Microsoft recently announced that a key new measure for its Azure data centres was energy inputs to data outputs. Thus Microsoft has directly linked energy usage as a means to define its compute power efficiency in terms of services delivered.

So what are our Kiwi companies doing to compete on this stage? Both Datacom and Spark use tools like artificial intelligence to monitor, control and measure their energy inputs. Historically it was simply a case of installing a few sub meters and a cost calculator (macro energy measurements). Today these companies aim to measure and monitor right down to the lightbulb (micro monitoring). The rise of the internet of things has made this ability to micro monitor even greater. As new data centres and factories are being built across the country, architects are being required to include in their plans, tools and products that embed internet of things, artificial intelligence and micro monitoring in the very fabric of the design.

Companies building factories in this country that do not think of micro monitoring of energy use as a strategic tool should be reminded that in the last few decades we exported more manufacturing jobs overseas than we created in all of IT. Ignorance of the strategic possibilities of micro energy monitoring is wilful blindness in a world where the Fourth Industrial Revolution is not only upon us, it is rapidly transforming the competitive landscape we work in.

by DavidSpratt | Jul 1, 2017 | ICT

A decade or more ago I used to defeat chess playing computers for a small wager. It was simple stuff really – just find a weakness and ruthlessly exploit it – in my mind computers were basically binary and thus “stupid”. Today chess masters are fair game for computers. My party trick is ancient history and I am frankly a little scared about what happens when computers can outsmart humankind. Terminator anyone?

Some would argue that we have nothing to fear. Others feel exactly the opposite.

Stephen Hawking recently wrote “The full development of AI could spell the end for the human race”.

Elon Musk – founder of PayPal, Solarcity and Tesla called it “Summoning the demon”.

The impact of AI in New Zealand

Putting aside visions of Arnie and terminators for the moment we should also look at the impact that AI might have on New Zealand businesses.

Most kiwi business owners and leaders are constantly aware of the need to innovate, optimise and seek competitive advantage by being cleverer than the guy overseas. Thus, we find ourselves asking:

- How do we get the best out of what we have?

- How do we employ better people and make them more effective?

- How do we use the limited space we have at our disposal?

- How do we get the machines that we paid heaps for to be more efficient?

The questions are endless but sadly the time and money we have is not. I cannot count the number of times I have spoken to business people who know what needs to be done to make companies better, faster or quicker but simply don’t have the spare time to do it.

Here is where Artificial Intelligence comes in. It not only analyses the data to answer the question but it can also act on the insight, often in real time.

Don’t believe me? How do you think Amazon remembers your book purchases and even title searches and then suggest others that may be of interest? AI also allows Amazon to identify your location, match it to the right supply chain service to execute the sale and delivery via the cheapest and most direct route.

Amazon’s arrival in Australia is causing tremors across the whole retail industry there. It’s not just books they sell, you name it, they have it, at a price too cheap to resist. At the heart of this frighteningly effective, multinational monster is Artificial Intelligence

We have always had AI – it has just been too expensive to make that much of a difference. Now it’s available as a service from the likes of Google (Google AI) and IBM – (Watson) and numerous clever startups.

The availability of world class AI a via Software as a Service model means that we don’t need supercomputers and massive budgets to take advantage of AI in New Zealand.

Next month I will describe examples of how AI is being used to optimise business’s use of energy and compute resources to save money and compete.

by DavidSpratt | May 5, 2017 | Energy, ICT

In the first two parts of this series I looked at what the internet of things (IoT) actually is and then at the Energy Management possibilities for businesses competing on the world stage.

In this, part three, of the series we get down to the nitty gritty of Manufacturing Production Management and how measuring energy flows and consumption can inform critical decisions.

I could make this complicated but if we really get down to the basics there are three main categories that require constant attention in a production environment: People, Processes and Technology.

People – Creating Feedback Loops

In the context of production management one of the most important variables is the performance of individual staff members. How someone uses equipment, works within a team, learns to adapt to new systems can make the difference between a highly profitable unit and one that is not.

What drives people’s decisions and actions will often come down to feedback loops. By using the Internet of Things to deliver energy monitoring information we can give people useful data about what is happening on their production line.

For example, if we can demonstrate that the team’s correct use of energy efficiency tools delivers a better product this not only reinforces their behaviour it also opens up the opportunity for them to take this information and find even better ways to improve efficiency.

How we use technology can be directly connected to the energy a unit or group of units consumes. If a lathe is running at full tilt throughout an eight hour shift does that necessarily mean that unit is being properly used? Or is the operator just running it on full because it that is what they were told to do when they first started years ago?

People make decisions at work every day. How you create feedback loops will inform those decisions more effectively and in doing so improved performance, job satisfaction and company results.

Processes

Every experienced Production Manager can tell you that each team on a production line is quite different and that their results vary considerably. The bigger question is “what causes this?”. By monitoring the flow of individual products and components through a production line we can identify bottlenecks, part shortages and defects quickly and effectively. With the Internet of Things we can break down a process into its smallest components, create various quality checkpoints along the way and eventually ensure near 100% accuracy, complete adherence to standards and instant identification of faults and tolerance variances.

Many would suggest that this is already the case in many well-run sites. But what happens off site with the parts we order and the products we ship?

The key to the internet of things is that our production process begins at the point where a component is ordered , right through the creation of unique SCU’s or products and all the way to the end user’s home, office or factory. This is because we can now potentially track billions of components throughout the supply chain at a cost much lower than we ever thought possible.

Technology

Remember the Internet of Things is not just adding an RFID tag to a unit and tracking it. It is about potentially billions of components that communicate. This can be back to a central point, with multiple other components, with the warehouse, the truck and of course with the end user.

By integrating Internet of Things components to the technologies we use in making things we can establish how one production line consumes energy at a fairly constant rate while another’s consumption appears to ebb and flow throughout the day.

In this instance we might have identified human errors, a malfunctioning device or quality issues with the parts or components being used on this line.

For the first time in our history we can easily measure our technology’s performance down to the tiniest detail. We are no longer limited by the number, location or stage of development of any component.

The Internet of Things opens a world of opportunities for us to deliver better quality at a lower cost and more reliably than ever before.