As renters and homeowners in the 1970s and 80s we were accustomed to hot water cylinder ‘ripple control’ – the mechanism whereby power companies assured us of a cold shower when we got home from work.

The trade-off was that households were able to operate stoves, lights and televisions without power cuts. Then along came the Clyde Dam and all this went away.

Until now.

If we take all our light vehicles off the road and replace them with EVs, this would increase our electricity demand by 20% (EECA Nov 2022). Add to this new ‘green’ data centres built by Google, Microsoft, AWS and our own IT companies, and this will likely add a further 10% to our current electricity needs. Our already stretched electricity supply infrastructure simply won’t cope.

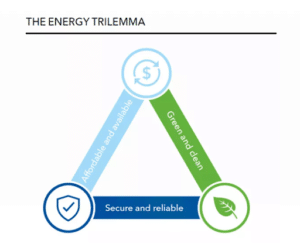

The Energy Trilemma is defined as the need to find balance between energy reliability, affordability, and sustainability and its impact on everyday lives.

Understanding the challenges to balancing these three core elements is vital to keeping the lights on, the economy operating and achieving goals such as Net Zero carbon emissions.

Energy Reliability

The energy system aimed at ensuring reliability in New Zealand is made up of three interconnected parts:

Generation which comes mainly from the dams in South Island Lakes.

Transmission – Transpower’s multibillion dollar electricity supply backbone, built mainly in the 1950s and 1980s on 30,000 properties, with 25,000 transmission towers supporting 11,000 kms of lines and their essential 170 substations.

Distribution – Delivering electricity to homes and businesses via 27 regional Lines Companies, most of whom are locally owned. These companies own the power poles, lines and transformers that bring electricity to our door.

These three elements are highly regulated and involve investments in assets worth billions of dollars.

Our whole energy system is funded by debt that must be paid for by current and future generations.

Who pays and when is the big issue here. Is it today’s user, their children or their children’s children?

This is called intergenerational debt servicing and presents huge challenges when deciding the fairest way to distribute the cost of assets that in some instances might have a useful life of fifty years or more – or in the case of dams much longer than that.

To make things worse, an emerging issue with these investments is the risk of what is known as ‘stranded assets.’ This happens when transformational technologies such as solar and wind based distributed energy systems makes further investment in centralised dams, transmission and distribution uneconomic. When this happens the debt remains but the ability to pay by leveraging (charging for) existing or new assets is reduced or disappears completely.

Affordability and Equity

The New Zealand economy is reliant on agriculture which in turn is reliant on energy. However, economic theory suggests that on a ‘user pays’ basis, a farmer in a remote location should pay more than an apartment dweller in a big city or town. After all it is, at first glance, far cheaper to provide an urban dweller power than it is to run kilometres of copper wire to a small number of farms down a rural highway.

Recent changes to the way costs are allocated for Transpower’s transmission backbone came up with the proposition that the further you are from the source of the power (the lakes) the more you pay because you accrue greater benefit.

This means that a dairy farmer in Northland pays much, much more for connection to the grid than a Southland farmer producing the same products with the same amount of electricity. It conveniently ignores the fact that three quarters of the population of New Zealand is in the North Island and therefore paid for at least this proportion of the massive costs of building our generation and transmission infrastructure in the first place.

Taking this economic puffery to its logical extreme we should be seeing city lines companies like Vector punishing those who are not living in the inner city by charging more for connections to their homes. Thank heavens for the Elected Trustee model that makes this kind of logic totally politically untenable.

While the Trust model provides a level of protection from purist economists, unelected energy officials aren’t as susceptible to the wrath of the voters.

Our government market regulator, the Commerce Commission, doesn’t even have an affordability or equity objective when addressing the electricity market. Instead, it’s ‘Right investments, Right Time at the right cost.’

What about doing ‘right’ by the rural communities generating enough food for 40 million people globally and generating exports in excess of $72 billion annually?

Sustainability

Electricity generated by gas fields, coal and oil fired power stations is expensive, carbon emitting and directly impacts the wholesale market price of electricity.

Over the past decade or so we have seen a steady decrease in their contribution to the country’s generation capacity as generators have switched off coal and gas fired capacity. A government ban on further oil and gas exploration and the rapid decline in our existing gas resources in and around Taranaki has placed even more pressure on our electricity supply.

The net result, as demand threatens to exceed supply, is that wholesale and forward prices are at record levels now and well into the future.

One answer to this supply issue might be Lake Onslow – pumped hydro – essentially a $17 billion, ten year project to deliver a giant hydro powered battery designed to help protect against hydro shortages.

Adding 1200 megawatts capacity (roughly an eighth of the country’s current peak capacity) would potentially help bring the volatile wholesale market for electricity back to some semblance of normality.

The Government has just made a decision to complete a $70 million business case on Lake Onslow. Add to that the $30 million they have already spent and it looks like this decision will be a major electricity industry inflexion point.

It’s difficult to see the GenTailers detaching themselves from the status quo and its associated super profits. As such it has been no surprise at all to see them aggressively highlight research from reports that paint the Onslow Project as an expensive and impractical idea.

What I have failed to see is any practical alternative being offered – other than the monopolists’ favourite – punishing vulnerable consumers into changing their behaviour by raising prices at peak time. This is not a great option when young consumers are juggling hungry children, bath times, winter heating bills and brutal mortgage interest rates, and dairy farmers have cattle lined up outside the sheds for milking.

Barring the embedded carbon costs of construction materials like steel and concrete, Onslow offers a sustainable opportunity to enhance the viability of inconsistent generation sources such as solar, wind and tidal generation. By providing a massive hydro based battery to store load as and when it is created, we could see wholesale prices back in the 8-12 cents per kw.

This would see the benefits of lower input costs flowing to farms, businesses and households instead of into the pockets of the gentailers and governments eager to feed off the dividends their super profits are providing.

- Part three of this series will address that most controversial of subjects – Water, Waste and Stormwater. Call it Three Waters if you like. I call it a right mess.